KNOB Issue 2

April 2024

Lena Müller visits sound designer Martyn Riley at Tokoro Studio to talk supper clubs, why you shoudn’t sit on a Le Corbusier sofa, and nomadic attitudes to living in the city.

Sound & Vision

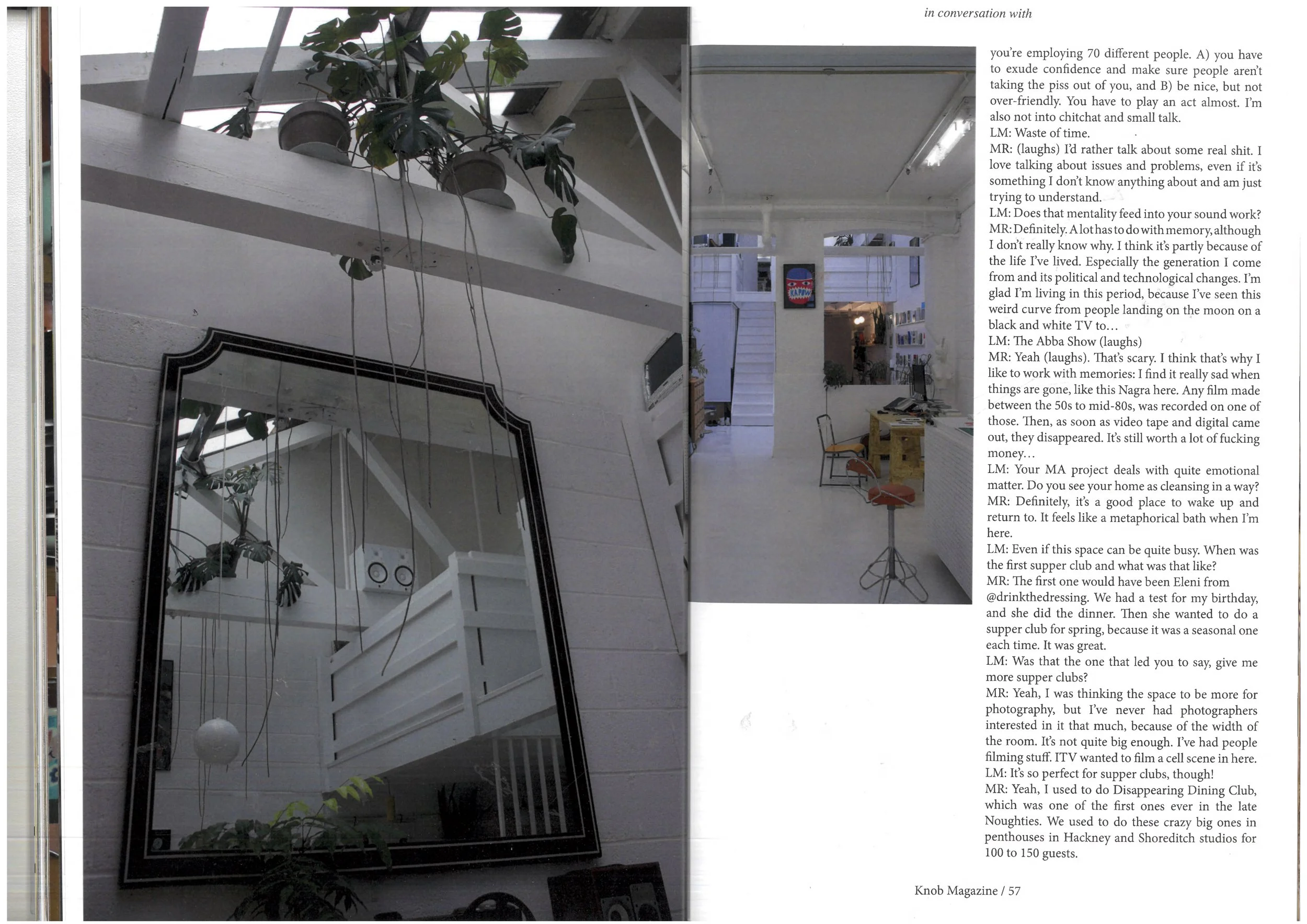

I arrive armed with an almond croissant at the graffitied gates of a warehouse community in North London. Behind the heavy metal door, at the end of a cobble-stoned courtyard, awaits Unit 13, otherwise known as Tokoro Studio. The white-washed and far-reaching space with lofty, high ceilings, is frequently rented out to host art exhibitions and supper clubs alike. Martyn Riley, a sound artist, proudly wearing Nike split-toe sneakers, houses, works, and hosts there.

Martyn has the calm and collected aura of a man who has lived many lives, and indeed he has: event and restaurant manager, bartender, writer, consultant, student, sound artist and a father. From organising music festivals like Glastonbury, Boiler Room and the Notting Hill Carnival, to managing swanky restaurants and running high-profile events for Dazed&Confused, Alexander McQueen and more, he is certainly no novice to dealing with a party.

Since moving to London from his native Derbyshire over 25 years ago, he has lived in a catalogue of areas until finally settling into Tokoro studio just before the first lockdown. He has since left hospitality at the bar and instead pursued the route of an experimental sound artist with a knack for memories and their materialisation, which recently culminated in his MA degree show. And surely, when he buzzed me in, I am greeted with a nearly hypnotic soundscape that escaped from a speaker in the front room and underlined the conversation that followed.

Fuelled by a cup of instant coffee, Martyn talks having strangers in his home, the endless struggle of money vs. mind and the joys of living a proto-nomadic life.

Lena: Is that a disco Tv?

Martyn: It’s not a Tv, it’s a Mac.

Lena: Well, this is where I show my age.

Martyn: (laughs) It’s an old iMac. I was home one night and drunk. I had ordered loads of little mirrors to mend a mirror ball in a different space and Amazon had sent ten times too much. Then I was sat at home on a Friday night and I looked at the old computer and just thought I should cover that.

Lena: I think it’s better than a disco ball.

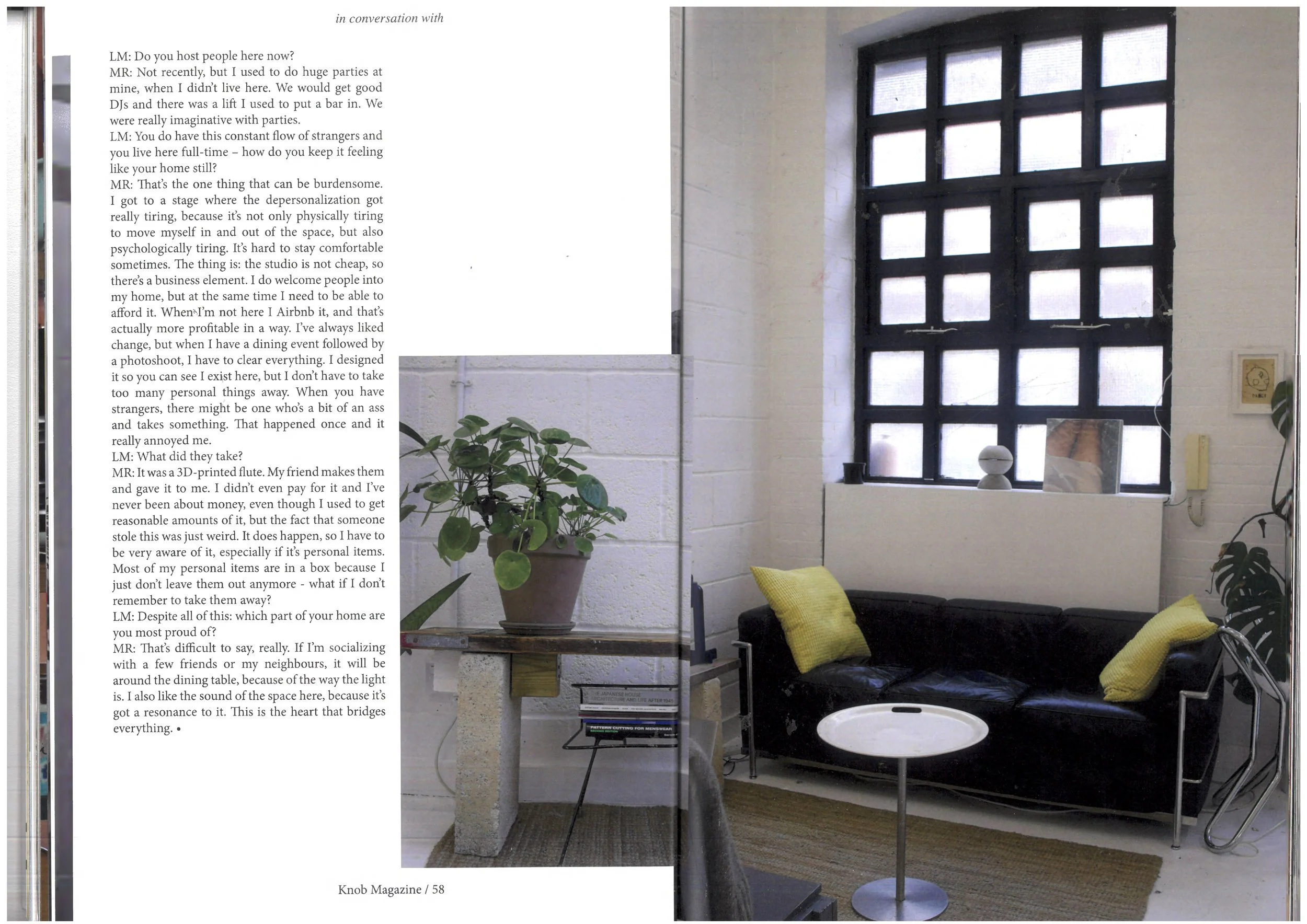

Martyn: I agree! Do you want to sit here? Even though that couch looks nice, it's not in the least comfortable. It's Corbusier. Those things are never designed to be sat on.

Lena: Yeah, that’s fine! Have you always imagined yourself living in a studio like this?

Martyn: That's funny actually, kind of… yes. Although, I’ve never really cared about property and bricks and mortar – much to the upset of my late father. I wouldn’t say I’m nomadic, but I’m proto-nomadic, where I don’t want to be barriered off and I have to be able to think, fuck it. I once lived in this really nice place in Camden, which was just behind Amy Winehouse’s house in the Murray Mews. When she died, it was full of Spanish people camping out and singing songs for about a year after.

Lena: What drew you to the Warehouses then?

Martyn: I had a dog, so I had to look at options, where I could be with my cocker spaniel Baxter, rest in peace. I came here and as soon as I saw the place, I just felt I had to live here. Even though, when you look back on the photos of the time, it wasn't that cool. Over six weeks, I painted everything you see white.

Lena: So, you basically painted the entire interior.

Martyn: Just me and it really was quite hard work. Even though it was white, it was a creamy white. I had a vision quite soon, of what it needed. I think partly, because of my experience. I made all the furniture and ripped out the kitchen; it was awful. I put in a commercial one, because I hate domestic sinks and cupboards – I want to see what I’ve got! I’ve not done any other substantial building work. The warehouses were all factories in the recession era, and they built these [side] walls to chuck'em up. A lot of it was rag trade and the one down the road used to build all the belts and buckles for the army. Now, it feels like a bizarre little village.

Another reason why I came here was that I crossed a bridge in my life where I left the industry that I had been doing for a couple of decades...

Lena: Hospitality?

Martyn: Yes, but also festivals and events. I used to run massive raves with thousands of people - it was insane. Then I had an epiphany where I thought this is just not pretty anymore (laughs). I remember working in restaurants was quite cool and sexy, but I got bored of that and the four walls started caving in on me. I decided to do something different and went down the sound route that I had taken before. It was about finding a space, where I could A, do that, and B, share it with people to benefit them, me and the community. Sounds a bit wanky (laughs).

Lena: It sounds romantic.

Martyn: Yes, it is quite romantic. People often want to be part of something, of a scene or group. I do a regular show called ADSR – the seventh one is in February. I usually have about 60 to 65 people coming and now, I get people asking if I am the ADSR-guy? (laughs)There's a template of how I do it now and how much social media bullshit I have to do. Although, I hate it when people say, oh you're really good at social media - I don't want to be good at this. But that's how people find out about it.

Lena: Sadly, these days that’s how people socialize. Would you say you’re more of an introvert or extrovert when it comes to that?

Martyn: I think I’m an introverted extrovert. I'm not someone who owns a room, but I love talking to and meeting people. When I was doing the events, I would get feedback that everyone's scared of me. It's because I couldn't be everyone's friend when you're employing 70 different people. A, you have to exude confidence and make sure people aren't taking the piss out of you, and B, be nice, but not overly friendly. You have to play an act almost. I’m also not into chitchat and small talk.

Lena: Waste of time.

Martyn: (laughs) I’d rather talk about some real shit. I love talking about issues and problems, even if it’s something I don’t know anything about and am just trying to understand.

Lena: Does that mentality feed into your sound work?

Martyn: Definitely. A lot has to do with memory, although I don't really know why. I think it's partly because of the life I've lived. Especially the generation I come from and its political and technological changes. I'm glad I'm living in this period, because I've seen this weird curve from people landing on the moon on a black and white Tv to…

Lena: The Abba Show (laughs)

Martyn: Yeah (laughs). That's scary. I think that's why I like to work with memories; I find it really sad when things are gone, like this Nagra here. Any film made between the 50s to mid 80s, was recorded on one of those. Then, as soon as video tape and the digital came out, they disappeared. It’s still worth a lot of fucking money…

Lena: Your MA project deals with quite emotional matter – do you see your home as cleansing in a way?

Martyn: Definitely, it's a good place to wake up and return to. It feels like a metaphorical bath when I'm here.

Lena: Even if this space can be quite busy: When was the first supper club and what was that like?

Martyn: The first one would have been Eleni from @drinkthedressing. We had a test for my birthday, and she did the dinner. Then she wanted to do a supper club for spring, because it was a seasonal one each time. It was great.

Lena: Was that the one that led you to say, give me more supper clubs?

Martyn: Yeah, I was thinking the space to be more for photography, but I’ve never had photographers interested in it that much, because of the width of the room. It’s not quite big enough. I’ve had people filming stuff. iTV wanted to film a cell scene in here.

Lena: It’s so perfect for supper clubs, though!

Martyn: Yeah, I used to do Disappearing Dining Club, which was one of the first ones ever in the late noughties. We used to do these crazy big ones in penthouses in Hackney and Shoreditch studios for 100 to 150 guests.

Lena: Do you host your people here now?

Martyn: Not recently, but I used to do huge parties at mine, when I didn’t live here. We would get good DJs and there was a lift I used to put a bar in. We were really imaginative with parties.

Lena: You do have this constant flow of strangers and you live here full-time – how do you keep it feeling like your home still?

Martyn: That’s the one thing that can be quite burdensome. I got to a stage, where the depersonalization got really tiring, because it’s not only physically tiring to move myself in and out of the space, but also psychologically tiring. It’s hard to stay comfortable sometimes. The thing is, the studio is not cheap, so there's a business element. I do welcome people into my home, but at the same time I need to for me to be able to afford it. When I’m not here I Airbnb it, and that’s actually more profitable in a way. I’ve always liked change, but I think it’s when I’ve got a dining event and then two days later a photoshoot and I have to clear everything. I designed it so you can see I exist here, but I don’t have to take too many personal things away. When you have strangers, there might be one, who’s a bit of an ass and takes something. That happened once and it really annoyed me.

Lena: What did they take?

Martyn: It was a 3D-printed flute. My friend makes them and gave it to me. I didn’t even pay for it and I’ve never been about money, even though I used to get reasonable amounts of it, but the fact that someone stole this was just weird. It does happen, so I have to be very aware of it, especially if it’s personal items. Most of my personal items are in a box because I just don’t leave them out anymore - what if I don’t remember to take them away?

Lena: Despite all of this: which part of your home are you most proud of?

Martyn: That’s difficult to say, really. If I’m socializing with a few friends or my neighbours, it will be around the dining table, because of the way the light is. I also like the sound of the space here, because it’s got a resonance to it. This is the heart that bridges everything.